By Leo Groarke

Summary

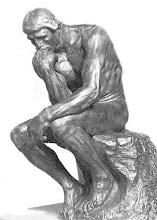

[193] The Socratic outlook is captured in Socrates' claim that 'the unexamined life is not worth living'. This outlook is vital for the well-being of a community and this may form the basis for an argument in favour of philosophical education.

The need for philosophical questioning is highlighted in the psychological experiments concerning authority made by Stanley Milgram. In these experiments individuals did not refuse to inflict pain on others when told to do so by an authority figure. [194] This tendency towards blind obedience to authority may help to explain the relationship between the Nazis and the German population. An unquestioning attitude towards political authority can thus have dangerous consequences. So Socratic questioning is vital for a well-balanced society.

In the Apology Socrates argued that if he were put to death it would be Athenian society, and not him, who would suffer the greater loss. His role as gadfly, although irritating, in fact benefited the community as a whole.

[195] Continual questioning in a society helps to correct old opinions and to generate new ideas. In modern society the impact of technology makes such questioning even more vital. In modern (nuclear) warfare a confused opinion can lead to the deaths of millions. Contemporary actions 'have more serious consequences than actions [did] in the past'. Moreover, technology creates a distance between one's actions and their consequences. [196] The way to overcome such 'distancing' is via Socratic reflection, reflection that must be undertaken by everyone in society.

In Plato's ideal state outlined in the Republic, such questioning by the general population is forbidden. [197] However this reflects his thought that the majority in society are not capable of genuine Socratic reflection, especially in the light of Socrates' execution. In order to make them capable, they need to be given the appropriate skills. This is where teaching philosophy has its role.

A specifically Socratic education should encourage Socratic reflection and questioning, rather than, say, the transfer of knowledge. This is the task for a philosophical education. Yet it is ironic that this is neglected in a democratic society like the USA, which is founded upon the principle that everybody should play a role in political decision making.

There are two parts in contemporary philosophical education that can help to promote this Socratic attitude. The first is informal logic, sometimes renamed 'critical thinking'. [198] There is no good reason why this should not be introduced at school level. The second is ethics. The author claims that:

The discussion of particular normative issues (nuclear weapons, women's rights, criminal justice, etc.) is essential to a satisfactory resolution of particular social issues.

Only with such discussion will individuals be able to make informed political choices. The realisation that, via informal logic and ethics, it will be possible to create a critical democratic society should form the basis for the promotion of the teaching of philosophy.

Comment

This article is a wonderfully naive eulogy to the democratic ideal. It assumes that, in a democratic society such as the USA, individual citizens can make real political choices and exert a genuine influence over the course of events. This naivety extends to the author's conception of the role of philosophy teaching, and is captured best in his claim that if enough university students discuss 'social issues' in seminars then the world will somehow become a better place. Moreover, if all US - or for that matter UK - citizens become amateur moral experts (pardon the expression) then their intelligent decisions at the ballot box will transform the way we live.

There are a number of issues that these claims raise, none of which are explicitly dealt within the article. Firstly there is the assumption that philosophy be 'useful' in some broadly social sense. The author appears to think that teaching philosophy requires some justification and he thinks that he has found it. He thinks that the primary reason why people are drawn to philosophy is to affect this sort of social change. No mention is made of, say, Aristotelian 'wonder' as an equally valid inspiration for philosophising.

Closely related to this is the way in which the author fails to distinguish between the image of Socrates as gadfly to society and the significance of the Socratic dictum that 'the unexamined life is not worth living'. The latter suggests, and is usually understood as, a call to self-examination, to be understood alongside Socrates' exhortation that one should 'take care of one's soul' [see e.g. Apology 30a-b]. Although Socrates may well have functioned as a gadfly attacking Athenian society, the purpose of this was to provoke others to take care of their own souls. In other words, it was to provoke others to engage upon an essentially personal philosophical project of self-examination. Socrates himself did not dare to make moral or political decisions, either for himself or for others, as he was only too aware of his own lack of knowledge and expertise in this area.

This, in turn, is closely related to a further point. Despite his references to the Apology and Republic, the author appears to have overlooked a central philosophical theme in Plato's early dialogues. Throughout these works Plato's Socrates searches for an expert in ethics, someone who can define what temperance is, what courage is, and so on. Yet such an expert is never found. Nor does Socrates ever claim to be that expert. The conclusion that one can draw from these dialogues is that expertise in matters moral and political is very rare, if indeed possible at all. In the Republic, Plato suggests that if anyone should hold political power it should be those with this expertise, i.e. the philosophers. Yet these are hypothetical philosophers in a hypothetical society, philosophers presumably more successful than Socrates in uncovering moral knowledge. All of this is far cry from the author's claim that university courses in informal logic and ethics will make the average citizen in a Western democracy a moral expert. Of course such courses may help to encourage cynicism and a distrust of those in genuine control, which can only be welcomed. In short, the author attempts to draw a positive and somewhat naive conclusion from the Socratic philosophical project, which is primarily negative and critical. What Socrates teaches (in Plato's early dialogues) is how to call into question the claims of ethical and political expertise made by others, but not how to run a Western liberal democracy. Attempting to justify the teaching of philosophy on the grounds that it will improve such a society seems to me to be deeply misguided.

[193] The Socratic outlook is captured in Socrates' claim that 'the unexamined life is not worth living'. This outlook is vital for the well-being of a community and this may form the basis for an argument in favour of philosophical education.

The need for philosophical questioning is highlighted in the psychological experiments concerning authority made by Stanley Milgram. In these experiments individuals did not refuse to inflict pain on others when told to do so by an authority figure. [194] This tendency towards blind obedience to authority may help to explain the relationship between the Nazis and the German population. An unquestioning attitude towards political authority can thus have dangerous consequences. So Socratic questioning is vital for a well-balanced society.

In the Apology Socrates argued that if he were put to death it would be Athenian society, and not him, who would suffer the greater loss. His role as gadfly, although irritating, in fact benefited the community as a whole.

[195] Continual questioning in a society helps to correct old opinions and to generate new ideas. In modern society the impact of technology makes such questioning even more vital. In modern (nuclear) warfare a confused opinion can lead to the deaths of millions. Contemporary actions 'have more serious consequences than actions [did] in the past'. Moreover, technology creates a distance between one's actions and their consequences. [196] The way to overcome such 'distancing' is via Socratic reflection, reflection that must be undertaken by everyone in society.

In Plato's ideal state outlined in the Republic, such questioning by the general population is forbidden. [197] However this reflects his thought that the majority in society are not capable of genuine Socratic reflection, especially in the light of Socrates' execution. In order to make them capable, they need to be given the appropriate skills. This is where teaching philosophy has its role.

A specifically Socratic education should encourage Socratic reflection and questioning, rather than, say, the transfer of knowledge. This is the task for a philosophical education. Yet it is ironic that this is neglected in a democratic society like the USA, which is founded upon the principle that everybody should play a role in political decision making.

There are two parts in contemporary philosophical education that can help to promote this Socratic attitude. The first is informal logic, sometimes renamed 'critical thinking'. [198] There is no good reason why this should not be introduced at school level. The second is ethics. The author claims that:

The discussion of particular normative issues (nuclear weapons, women's rights, criminal justice, etc.) is essential to a satisfactory resolution of particular social issues.

Only with such discussion will individuals be able to make informed political choices. The realisation that, via informal logic and ethics, it will be possible to create a critical democratic society should form the basis for the promotion of the teaching of philosophy.

Comment

This article is a wonderfully naive eulogy to the democratic ideal. It assumes that, in a democratic society such as the USA, individual citizens can make real political choices and exert a genuine influence over the course of events. This naivety extends to the author's conception of the role of philosophy teaching, and is captured best in his claim that if enough university students discuss 'social issues' in seminars then the world will somehow become a better place. Moreover, if all US - or for that matter UK - citizens become amateur moral experts (pardon the expression) then their intelligent decisions at the ballot box will transform the way we live.

There are a number of issues that these claims raise, none of which are explicitly dealt within the article. Firstly there is the assumption that philosophy be 'useful' in some broadly social sense. The author appears to think that teaching philosophy requires some justification and he thinks that he has found it. He thinks that the primary reason why people are drawn to philosophy is to affect this sort of social change. No mention is made of, say, Aristotelian 'wonder' as an equally valid inspiration for philosophising.

Closely related to this is the way in which the author fails to distinguish between the image of Socrates as gadfly to society and the significance of the Socratic dictum that 'the unexamined life is not worth living'. The latter suggests, and is usually understood as, a call to self-examination, to be understood alongside Socrates' exhortation that one should 'take care of one's soul' [see e.g. Apology 30a-b]. Although Socrates may well have functioned as a gadfly attacking Athenian society, the purpose of this was to provoke others to take care of their own souls. In other words, it was to provoke others to engage upon an essentially personal philosophical project of self-examination. Socrates himself did not dare to make moral or political decisions, either for himself or for others, as he was only too aware of his own lack of knowledge and expertise in this area.

This, in turn, is closely related to a further point. Despite his references to the Apology and Republic, the author appears to have overlooked a central philosophical theme in Plato's early dialogues. Throughout these works Plato's Socrates searches for an expert in ethics, someone who can define what temperance is, what courage is, and so on. Yet such an expert is never found. Nor does Socrates ever claim to be that expert. The conclusion that one can draw from these dialogues is that expertise in matters moral and political is very rare, if indeed possible at all. In the Republic, Plato suggests that if anyone should hold political power it should be those with this expertise, i.e. the philosophers. Yet these are hypothetical philosophers in a hypothetical society, philosophers presumably more successful than Socrates in uncovering moral knowledge. All of this is far cry from the author's claim that university courses in informal logic and ethics will make the average citizen in a Western democracy a moral expert. Of course such courses may help to encourage cynicism and a distrust of those in genuine control, which can only be welcomed. In short, the author attempts to draw a positive and somewhat naive conclusion from the Socratic philosophical project, which is primarily negative and critical. What Socrates teaches (in Plato's early dialogues) is how to call into question the claims of ethical and political expertise made by others, but not how to run a Western liberal democracy. Attempting to justify the teaching of philosophy on the grounds that it will improve such a society seems to me to be deeply misguided.

No comments:

Post a Comment